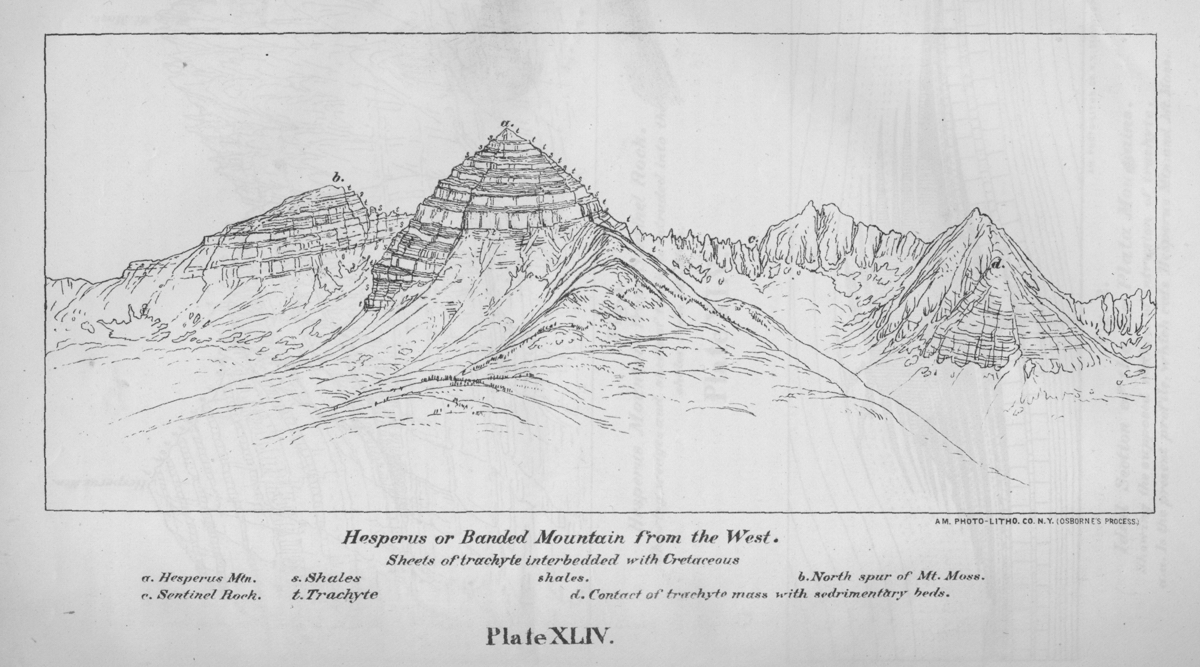

In the vicinity of Mount Moss, a vast number of sheets and masses of trachyte have been forced into the yielding and nearly horizontal Cretaceous shales. The sheets in most cases follow approximately the planes of bedding.

The intrusion of sheets and wedges, however, is most strikingly illustrated in Mount Hesperus. Between timber-line and the summit there is an alternation of trachyte sheets with the shales . . . In the upper 1,500 feet there are twelve distinct layers of trachyte, some having a thickness of from 30 to 40 feet, others of not more than a few inches.

Annual Report for 1875 (Hayden 1877, 270)

The La Plata Mountains: Hesperus or Banded Mountain from the West

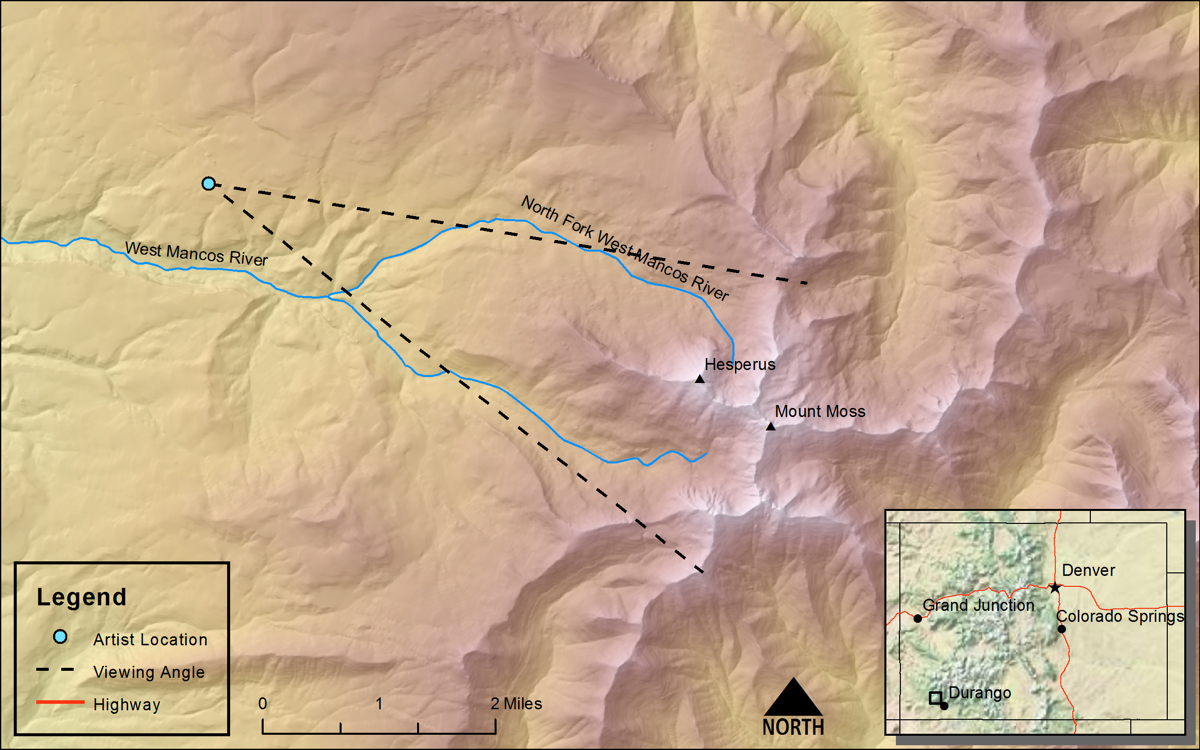

(Annual Report for 1875 Field Season Hayden 1877 - Plate XLIV, page 270)DRAWN/TAKEN FROM GEOGRAPHIC COORDINATES: LATITUDE: 37°28′21′′ N | LONGITUDE: 108°09′48′′ W | UTM zone 12N | 750,728 mE | 4,150,922 mN

VIEW ANGLE: East | COUNTY: Montezuma | NEAREST CITY: Mancos

This is a sketch drawn from the flatter country west of Hesperus. The banding of the mountain is obvious and makes Hesperus one of the most distinctive mountain sites in Colorado. Alternating beds of volcanic intrusive sills and altered shale create the banded effect.

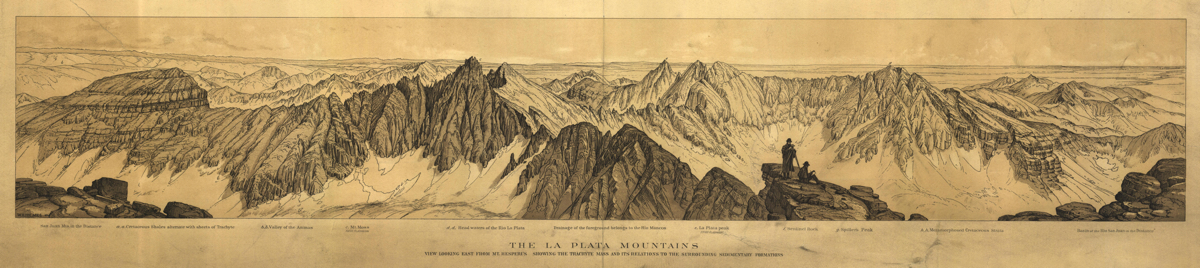

View from Hesperus Mountain

(Atlas Hayden Survey 1877 - Sheet XX)DRAWN/TAKEN FROM GEOGRAPHIC COORDINATES: LATITUDE: 37°26′42′′ N | LONGITUDE: 108°05′08′′ W | UTM zone 12N | 757,388 mE | 4,147,971 mN

VIEW ANGLE: North-northeast clockwise through south-southeast | COUNTY: Montezuma | NEAREST CITY: Mancos

The Hesperus Mountain summit (13,232 feet) is a rocky and rubbly apex. The close-up view of the nearby La Plata Mountains is almost intimate from so high a perch.

William Henry Holmes thought that Hesperus Mountain (13,232 feet) was the most western high mountain in Colorado and one of the most striking—deserving of a mythical name. He thus named it Hesperus—in Greek mythology this means “evening star” and alludes to the far west. Hesperus and its near neighbors have had a confusing nomenclature even into modern times. Many still call Hesperus Banded Mountain because of its dramatic layered appearance, which will be discussed at length below. But the United States Geological Survey on its 1963, La Plata 7.5-minute topographic quadrangle calls the mountain just to the east-northeast of Hesperus Banded Mountain (13,062 feet). And the current official name of this second Banded Mountain is now Centennial Peak.

Possibly the oldest name given to Hesperus Mountain comes from the Navajo belief in four sacred mountains of which Hesperus is one. Hesperus, or Dibé Nitsaa (Big Sheep Mountain), was the Navajo’s Sacred Mountain of the North. Blanca Peak (Tsisnaasjini’) in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains of Colorado is the Sacred Mountain of the East; Mount Taylor (Tsoodzil) in New Mexico is the Sacred Mountain of the South; and, the San Francisco Peaks (Doko’oosliid) just north of Flagstaff, Arizona, is the Sacred Mountain of the West. These four mountains mark the homeland of the Navajo, and they are repeatedly mentioned in the Navajo’s traditional Blessingway.

The geology of the La Plata Mountains in general and Hesperus Mountain specifically is singular in its origins and its visual results. The La Plata Mountains are the far southwestern subrange of the larger San Juan Mountain system. This small, nearly circular set of uplands started out as a large structural dome created by massive intrusions of molten rock. The La Plata Mountains did not have the explosive volcanic events that the main San Juans experienced, but a more quiescent, localized molten injection. These magmatic injections in the La Plata Mountains occurred during the general geologic upheaval of the Laramide Orogeny at the end of the Cretaceous. The intrusions probably lasted from 2 to 3 million years and created the striking banded effect seen in Hesperus Mountain, Mount Moss [(c) on the panorama], Centennial Peak, Sharkstooth Peak, and other summits neighboring Hesperus. Hot, liquid magma flowed from vents deep within the earth, up weak zones, and eventually horizontally into the already-in-place Cretaceous shales of the Mancos formation. This interlayered magma cooled creating hard, erosion-resistant beds. The heat from the molten sills altered the soft and friable country rock (the already-in-place Mancos shales) by hardening them through a process called contact metamorphism. This was relatively weak, low-level metamorphic activity, and fossils that can be easily seen throughout the Mancos shale were not totally destroyed and are still recognized in the new slatelike rock that the metamorphism produced. A more vigorous metamorphism would have altered beyond recognition any and all fossil evidence.

While climbing Hesperus Mountain, one sees substantial evidence of this slaty material. It makes up the dark bands in contrast to the lighter-colored, more erosion-resistant trachytes described by Holmes in the Annual Report. Many observers erroneously talk about the “obsidian” dust or rock, but there is no obsidian or any other extrusive rock in the area. The dust is the weathered remnants of the fine-grained, nearly black slate. The layering of the slate and the trachyte creates an intricate pattern of interbedding and makes the climb up Hesperus a series of cliffs and slopes, cliffs and slopes. Holmes describes it as “a sort of dovetailing . . . that might be illustrated by setting two combs so that the teeth should alternate” (Hayden 1877, 270). The bands are most visually striking from afar as seen in the first drawing/photograph pair, originally titled “Hesperus or Banded Mountain from the West.” The mountain is slightly obscured in the photo because the forest has grown substantially since Hayden’s time. When Holmes did the drawing, this area was less wooded and the trees that did exist were smaller.

There is little human occupancy in the La Plata Mountains—they are just too rugged and difficult to settle. The largest burst of population started in 1873, when gold ore was discovered along the La Plata River, which flows from north to south just beyond the mountains in the drawing/photo from the top of Hesperus Mountain. In fact, Mount Moss (labeled on the drawing) was named by William Henry Holmes for one of the main promoters/prospectors in the region. In Holmes’s own words in his Annual Report for 1875, “I have named it Mount Moss after the indomitable Capt. John Moss, of Parrott City” (Hayden 1877, 268). Moss was the prime mover in getting outside investment for the large, thirty-six-square-mile mining district he established. Moss convinced a California mining investor named Tiburcio Parrott to back the development of the Parrott mining district. The town at the center of the district and the mountain just a mile and a half west of the town were both named after Parrott. Today few if any structures remain of Parrott City or of the more lucrative and well-established camps of La Plata and Mayday.

There was no productive mining activity near Hesperus Mountain, but the La Plata River Valley produced small amounts of gold, silver, and several other valuable metals. The veins where the native ores and the tellurides were found were emplaced by massive hydrothermal activity during the volcanic injections that created the famous banding seen in the mountains. These were the same intrusions that produced the doming and uplift of the entire La Plata Range.

The mining that occurred was on land that by the Brunot Treaty ratified by Congress in 1874 was ceded from the several Ute bands to the US government. The two Ute Indian reservations of Colorado (the Southern Ute Reservation and the Ute Mountain Ute Reservation) did not yet exist. Only after the 1879 Meeker Massacre and the “Utes Must Go” campaign were the reservations established and all other lands reverted to the US government, the miners, and other settlers. The Southern Ute Reservation lies just a few miles south of Hesperus and the La Plata Mountains. There is no question that the Utes used the La Plata, at least for hunting purposes. And it is obvious that the Navajo viewed the area as part of their traditional lands. But there is little evidence that the Anasazi of the Mesa Verde area or the more ancient Paleo-Indians used this region. Some Paleo-Indian artifacts (almost exclusively projectile points) have been found in places surrounding the La Plata Mountains, but as of today no Paleo-Indian artifacts have been recovered near Hesperus Mountain.

The panorama shows almost an intimate view of the small La Plata Range. The area is rugged and not well known among Coloradans. The views, however, are stunning and the landscapes precipitous.

© 2016 by University Press of Colorado

© 2016 by University Press of Colorado