. . . the great Sawatch range formed the central portion of a gigantic anticline. . . . The general elevation of the Sawatch range for 60 to 80 miles is 13,000 to 14,000 feet above the sea at this time, and it is highly probable that hundreds and perhaps thousands of feet have been removed from the summit . . . inconceivable to a finite mind.

Annual Report for 1874 (Hayden 1876, 47)

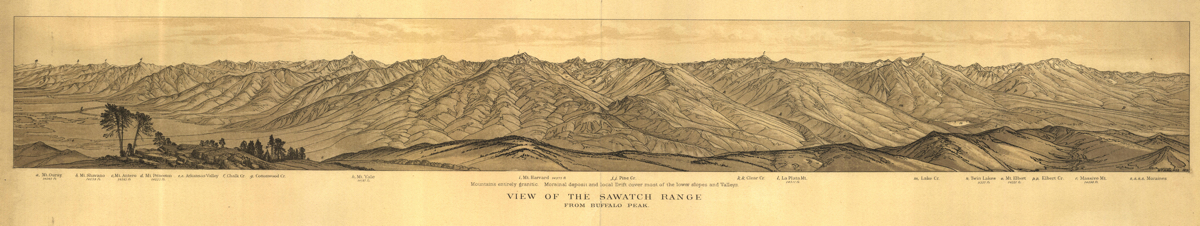

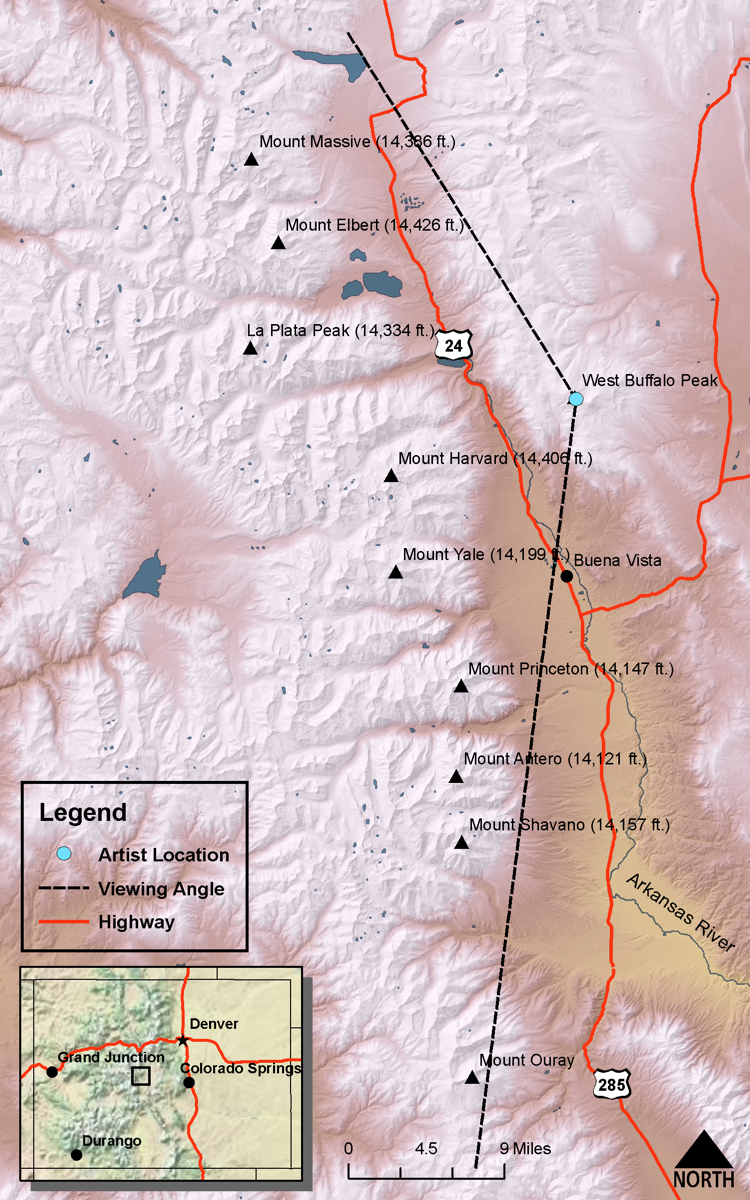

View of the Sawatch Range

DRAWN/TAKEN FROM GEOGRAPHIC COORDINATES: LATITUDE: 38°59′31′′ N | LONGITUDE: 106°07′26′′ W | UTM zone 13N | 402,660 mE | 4,316,286 mNVIEW ANGLE: South-southwest clockwise through north | COUNTY: Park/Chaffee | NEAREST CITY: Buena Vista

The photo and drawing were taken from West Buffalo Peak (13,326 feet). This stunning panorama was drawn by William Henry Holmes. This is probably the most expansive view of all those drawn for Hayden’s Survey; it covers well over sixty miles from Mt. Ouray in the south (left) to Mt. Massive in the north (right).

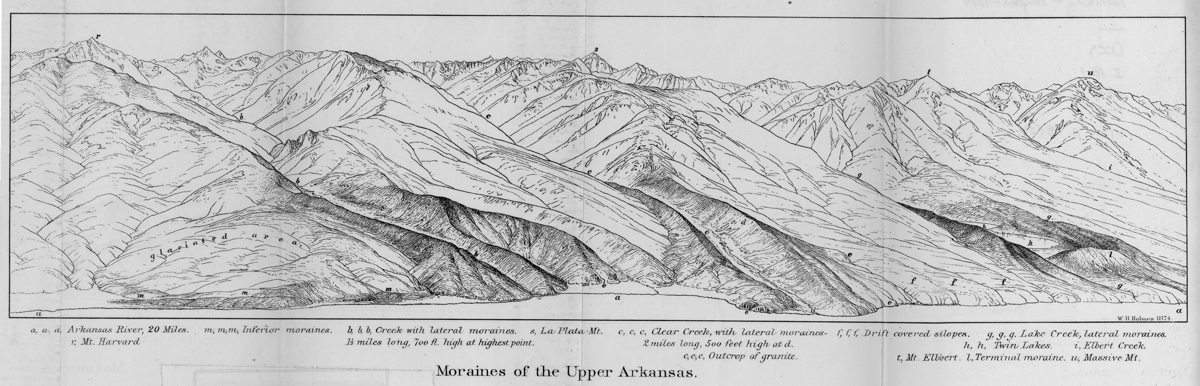

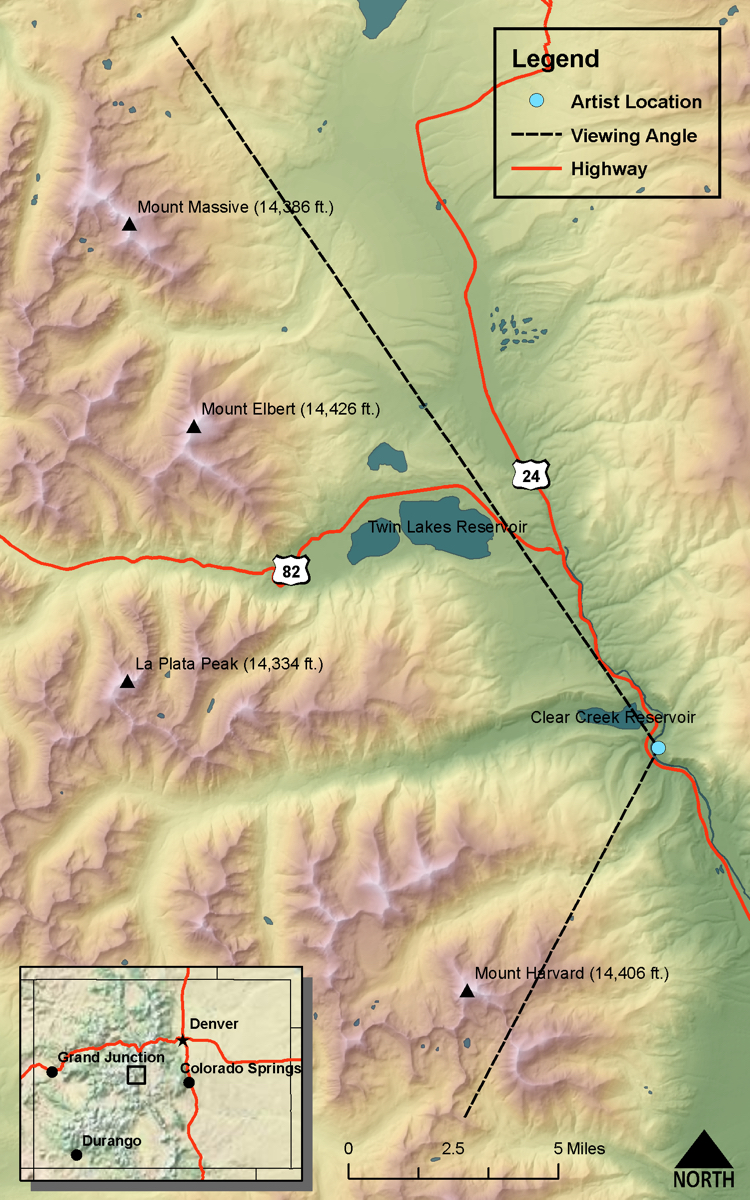

Perhaps the most interesting and novel features of this region are the great morainal deposits, the remains of ancient glaciers . . . The finest illustration occurs in the valley of Clear Creek, a small stream that flows into the Arkansas River from the Sawatch range, about six or seven mills [sic] below Lake Creek.

Annual Report for 1873 (Hayden 1874, 51)

Moraines of the Upper Arkansas

DRAWN/TAKEN FROM GEOGRAPHIC COORDINATES: LATITUDE: 39°01′37′′ N | LONGITUDE: 106°14′15′′ W | UTM zone 13N | 392,830 mE | 4,318,510 mNVIEW ANGLE: Southwest clockwise to north-northwest | COUNTY: Chaffee | NEAREST CITY: Granite

This is one of the few views that have been from a point that does not really exist. The photo position was the closest real viewpoint to where the drawing was done. The photo shows Clear Creek Reservoir, which of course did not exist during Hayden’s time.

“Now This Is Colorado”—this phrase is carved on numerous wooden signs that welcome today’s drivers along any highway leading into Chaffee County, Colorado. With apologies to Saguache County, which sits at the very far left of the “View of the Sawatch Range” drawing and Lake County, which contains both Mount Elbert [(o) on the panorama] and Mount Massive (r) on the far right, this landscape rendering is really of the western half of Chaffee County. The Sawatch Range, of which the more famous Collegiate Peaks are a subrange, is the home of a plurality of 14ers in Colorado—fifteen total in the range with ten clearly visible in this drawing/photo. These include Mount Elbert (14,433 feet and the highest peak in Colorado), Mount Massive (14,421 feet, second highest), Mount Harvard (14,420 feet, third) [i], La Plata Peak (14,336 feet) [l], Mount Antero (14,269 feet) [c], Mount Shavano (14,229 feet) [b], Mount Princeton (14,197 feet) [d], Mount Yale (14,196 feet) [h], Tabeguache Peak (14,155 feet), and Mount Columbia (14,073 feet). This view of the massive front of the Sawatch Range stretches sixty miles from just south of Mount Ouray at the far left to just north of Mount Massive outside of Leadville. The Arkansas River Valley, though hidden by the foreground terrain, runs along the entire distance in the valley below. Its headwaters are at Tennessee Pass north of Leadville, and it turns sharply east just across the valley from Mount Shavano.

The geology of the scene is less complex than in many of the mountain ranges of Colorado, although that is only relative. Hayden and his survey were perceptive in recognizing that the scene was part of a “grand anticline”—a large, upward-arched geologic structure of bent sedimentary rocks. The strike of the anticline ran from the headwaters of the Arkansas all the way to the big bend, where the river turns dramatically east just north of Poncha Pass. The eastern limb of the anticline runs along the western edge of South Park, where there is still considerable evidence of the anticline in the sedimentary beds that lie there. The “grand” anticline structure arched up and over the upper Arkansas Valley and the western limb is tens of miles to the west of the valley all along the contact between the Elk Mountains and the Sawatch Range centered on the upper Taylor River and Taylor Park. Erosion has stripped nearly all of the arched sedimentary strata from this western limb. Hayden describes the Sawatch as the “central mass or axis” of this super anticline. He and his other geologists also write about the incomprehensible amount of erosion that has taken place to remove the overlying sediments of this geologic structure.

One of the strengths, and also one of the weaknesses, of Hayden’s work is that he is very good, maybe too good, at simplifying the complex nature of the Colorado Rockies. The strength of this practice was creating an understanding of what happened to form the mountain system that most people, even nonscientists, could appreciate. He states flatly, for example, that his grand anticline “seems to illustrate a statement that I have often made . . . in regard to the simplicity of the structure of the eastern portion of the Rocky Mountain region” (Hayden 1874, 49). The weakness was omitting much of the important detail and understanding of complex processes. To be fair, though, many things could not have been known by Hayden in the era in which he worked.

One glaring example of this simplification is the Arkansas River Valley and Hayden and his crew’s belief that the river alone carried away the thousands of feet of sediment to create the large valley that exists today. He was partly correct, of course—the river has eroded and carried large amounts of sediment away—but this explanation cannot account for all of the loss of this rock. Only in the last several decades, since the theory of plate tectonics has been well developed and all but made into a natural law, has a more complete explanation for the valley gained wide acceptance.

The upper Arkansas Valley was recently, in geologic terms, connected structurally and hydrologically with the San Luis Valley just to the south over Poncha Pass. In fact the Arkansas flowed into the Rio Grande drainage system until recent (in the geologic time frame) uplifts of the Poncha Pass area occurred. More dramatically, the Arkansas Valley, the San Luis Valley, and the Rio Grande Valley into New Mexico are all part of an extended Miocene-Pliocene-age tectonic rift zone in the crust of the earth. Faulting throughout the San Luis Valley and the upper Arkansas Valley made both of these structures what geologists call grabens, relatively downthrown areas in relation to the uplifting of the mountains on either side. The rifting of the Rio Grande Valley is certainly evident near Taos, New Mexico, where large basalt flows from the rift zone have flooded and created the mesa there. One can easily see this geologic phenomenon by standing on the bridge crossing the Rio Grande a few miles north of Taos. The layers of several basalt flows visible are obvious even to a geologic neophyte. Some geologists have speculated that the rift extends considerably north of the Arkansas Valley—maybe as far as Steamboat Springs. The mainstream theory, however, is that the northern limit is really the northern end of the Arkansas Valley.

Hayden also makes a blanket statement that the entire Sawatch Range is composed of granites with some metamorphic rock. He is correct as far as he goes. The northern half of the range down to just north of Mount Princeton is older metamorphic rocks (gneiss, schist, and migmatites ≈ 1.7 to 1.8 billion years old) with some minor intrusions of younger granite—much more extensive metamorphism than Hayden described. From Mount Princeton south the rock is a much, much younger, Tertiary age intrusive granite/diorite that is between 20 and 40 million years old.

Because of the extensive faulting along the western edge of the Arkansas Valley, numerous hot springs have developed. The two most well known are the Cottonwood hot springs along Cottonwood Creek west of Buena Vista and the Mount Princeton Hot Springs along Chalk Creek south of Buena Vista. The superheated water at the Mount Princeton springs has created a geologic misnomer—the famous Chalk Cliffs on Mount Princeton, and hence the name of Chalk Creek, are not chalk at all even though they do look chalk-like. They are really the remnants of what was left over after the hot waters weathered the Tertiary intrusives and removed all the mineral components of the rock except the whitish, unconsolidated silica-rich clay called kaolinite.

In the 1860s and early 1870s, there was some mineral exploration and extraction, especially placer mining along the numerous streams coming off of the Sawatch Range. This era of mining never became lucrative and had just about played out by the time the Hayden Survey came to the region. Hayden flatly states, “The decline of the mining interest has caused the upper portion of the valley to be almost entirely deserted” (Hayden 1874, 50). Only a few short years after this statement, one of the most famous and valuable mineral finds ever in Colorado was made at Leadville. Ironically, the boom for this silver (mostly) and gold strike soared in 1878 and 1879, just after the Hayden finished his survey of Colorado.

There had been intensive and widespread glaciation in all of the high mountains of Colorado during the Pleistocene epoch as discussed in many of the sections in this publication. But nowhere in the state was the glacial erosion and deposition greater than that highlighted by Hayden in the Sawatch Range and along the western side of the Arkansas Valley. Alpine glaciation of the type Colorado experienced formed in already-existing mountain and valley terrain. Glaciers take advantage of the mountains’ already extant topography that captures and concentrates increased snowfall aided by lower, overall temperatures. Most valley glaciers begin through increased snow accumulation in small depressions high up the mountains near the summits. The ice that eventually forms from the compression of the ever-increasing snow depths starts to slowly move downslope, eroding the depression over many centuries and creating what we call the glacial cirque—or “excavated amphitheater,” to use Hayden’s term. More snow accumulates and becomes ice, and the entire mass moves down valley removing already weathered rock and, over time, weathering and eroding more and more rock from the valley walls and floor.

The rock debris is carried by the ice as the valley continues to erode to a flat-bottomed, U-shaped cross-section. Eventually, the ice retreats when temperatures moderate and/or snowfall decreases in the long term. Because ice is capable of transporting a wide range of sizes of mineral debris, when the ice retreats it deposits large masses of everything from clay-size particles to room-size boulders. These deposits are historically called drift, a euphemism concocted by people who thought the “big flood” of Noah’s fame had icebergs carrying rock debris around until the floodwaters receded. Hayden, and even more modern geologists and geomorphologists, still refer to “drift” even though the more technically correct term is “till,” which when deposited by the ice creates landforms called moraines.

A note on the “Moraines of the Upper Arkansas” drawing/photograph in the Clear Creek area is called for here. This drawing is another case in which it could not have been an exact rendering of the landscape as seen by the artist; one cannot see this view while standing on any piece of ground. The perspective of the work would have put the artist in midair between two prominent points of land across the valley from Clear Creek. The photo was taken from the point that is closest to what the artist drew. Also, the building of Clear Creek Reservoir has changed much of the foreground and reworked a large amount of the glacial debris near the valley floor.

Massive moraines can be seen in the “Moraines of the Upper Arkansas” drawing/photo centered on Clear Creek. The moraines closest to the valley are called “end moraines,” places where the stagnant snout of the glacier dropped large amounts of till. Ground moraines form along the valley bottom, where a thin veneer of mineral debris is deposited as the glacier retreats more rapidly. Lateral moraines [(c and d) on the panorama] along the sides of the valley can be seen in the landscape drawing by William Henry Holmes.

From just north of Buena Vista and especially near Clear Creek and Twin Lakes, there are huge moraines deposited along the western edge of the valley. It was once speculated that there were only four main glacial advances, or stades, during the Pleistocene—each named after a state that was affected by continental glaciation (the Wisconsin age advance was the latest). But closer and more intensive research has shown that there were many stades, some estimates up to twelve, which occurred in Colorado and the West. The moraines at Clear Creek and Twin Lakes are dated from the latest two stades—the Bull Lake and the younger Pinedale. Both names come from sites in the Wind River Mountains of Wyoming, where they were first described. Till from earlier stades has been eliminated by the advance of younger glacial episodes.

South of Buena Vista there is a somewhat different type of glacial deposit. Ice does not sort its deposits by size/weight, but running water does. As swift-flowing streams start to lose velocity when they exit the steeper mountain valley, they drop the larger, heavier rock debris first. More slowing allows smaller and smaller material to be deposited in decreasing size sequence. Eventually, only the smallest, clay sized particles remain in the nearly still water. By this sorting and nonsorting, geomorphologists and geologists can determine the nature of what the depositional environment was. The material south of Buena Vista is mostly this water deposited and sorted “outwash” debris. These too are Bull Lake and Pinedale–aged deposits (see next section).

“Now This Is Colorado” might just refer to the Arkansas Headwaters Recreation Area that was established to help preserve and promote the various recreational activities along the river valley. These include some of the best white-water rafting in the state; some of the premier, gold-medal trout fishing; hiking; mountain biking; and, of course, mountaineering. The mountaineering here is not as technical as some of the areas that are discussed in here (the Central Elk Mountains, section 12 and the San Miguel Mountains, section 17, for example). In fact, many of the ascents, even of the 14ers in the Sawatch Range, are no more than long, hard, high-altitude hikes. Some of the peaks even have trails all the way to the top. But this lack of technical rigor does not lessen the fact that the Sawatch is a high-mountain destination and probably worthy of the Chaffee County axiom. Obviously, the survey thought this was a special place. The writings about the Arkansas Valley and the Sawatch Range are extensive and detailed.

© 2016 by University Press of Colorado

© 2016 by University Press of Colorado