In the vicinity of Bear Creek and its branches . . . We may say here that the coarseness of the sediments of the lower beds of the red group is not the only evidence of the disturbed condition of the waters that deposited them; all through the group are quite remarkable illustrations of irregular and oblique lamination.

Annual Report for the 1873 Field Season (Hayden 1874, 30-31)

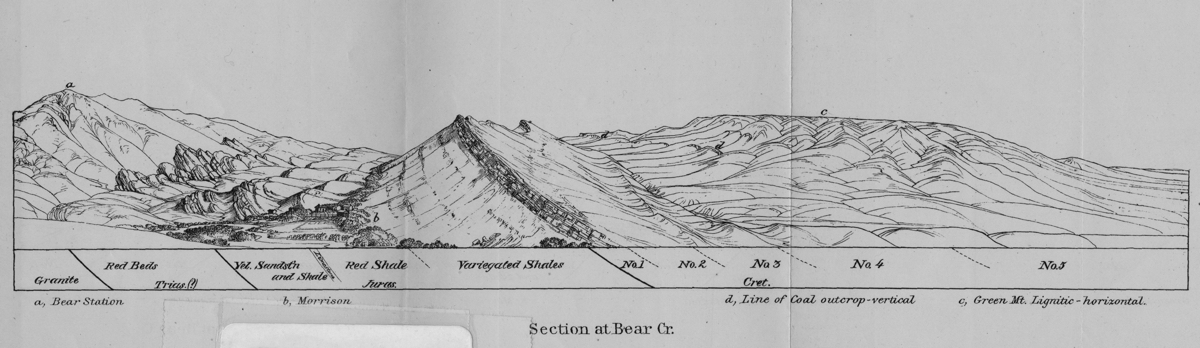

Section at Bear Creek/Morrison

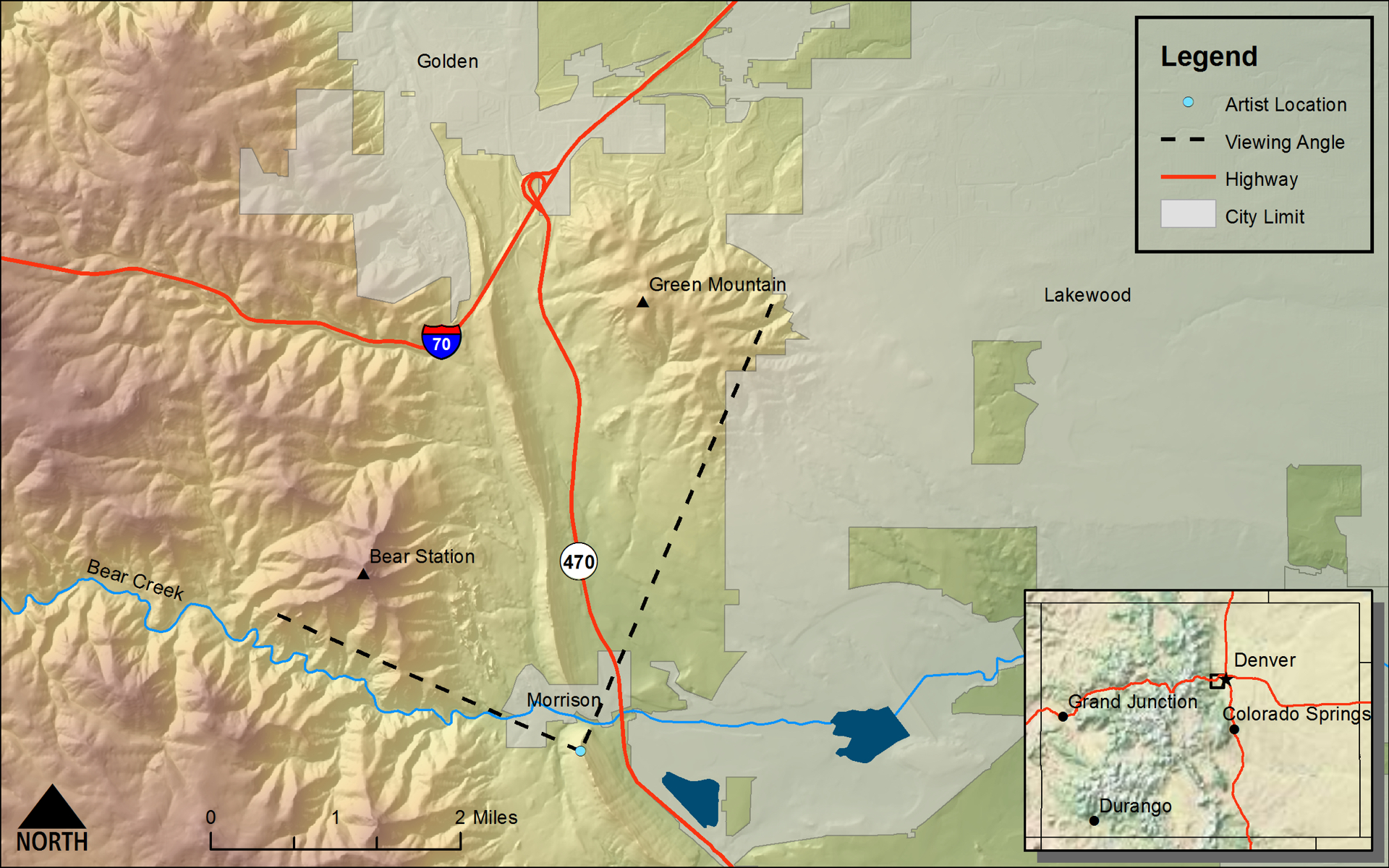

(Annual Report for 1873 Field Season [Hayden 1874], Scene E, Section at Bear Cr.)DRAWN/TAKEN FROM GEOGRAPHIC COORDINATES: LATITUDE: 39°38′59′′ N | LONGITUDE: 105°11′21′′ W | UTM zone 13N | 483,930 mE | 4,388,765 mN

VIEW ANGLE: Northwest | COUNTY: Jefferson | NEAREST CITY: Morrison

This view was taken from the far northwestern top of Mount Glennon that is part of the gateway from the east to the small town of Morrison. The current location of the Red Rocks amphitheater venue is at the left of the image where the scalloped-looking rock formations sit. The valley on the left side of this drawing/photo is one of the first locations for major dinosaur fossil discoveries during and after the Hayden Survey.

The landscape sketch from Hayden’s 1874 report “Section at Bear Cr.” fits comfortably into the series of landscape sections he published in the survey that stretch along the Front Range. Hayden and his survey spent a great deal of time along the base of the Front Range, and they produced an interesting sequence of landscape drawings from the Wyoming border to south of Cañon City. This particular section is no exception as it looks north from the top of Mount Glennon just east of Morrison. The dominant characteristic of this drawing is the prominent hogback just to the left of center. According to the legend at the bottom of the sketch, this hogback is labeled “Cret. No. 1”; in the current geologic nomenclature it is the Dakota Sandstone. The Dakota is found throughout the Mountain West and is a very erosion-resistant rock that provides protection for softer rock, such as shale, that lies below it. These weaker “variegated shales,” as indicated on the sketch, are now referred to as the Morrison formation. Point “a” on the sketch is the top of Mount Morrison, a prominent peak in the crystalline rocks of the Front Range proper. On the horizon to the back left at “c” is “Green Mt. Lignitic—horizontal” beds. This mesalike mountain is a Tertiary sedimentary rock that contains at least a trace of coal. Today the rock is called the Green Mountain conglomerate.

The scene’s most intricate landscape elements lie between the main hogback and the mountains to the west. Here sits the small hamlet of Morrison (b) and the erodible rocks of the Ralston Creek and Lykins formations. The distinctive scalloped rocks are the famed “Red Beds” consisting of the Lyons formation, and especially in this case, the Fountain formation. The Fountain formation is the one referred to by Hayden in the opening quote. It is a conglomerate, made from the turbulent flow of water carrying a large amount of varying-sized debris. It is cited as evidence of the “Ancestral Rockies” that existed circa 300 million years ago (mya) to 270 mya. Bear Creek, which carved the water gap just to the forefront of the Dakota hogback, can be seen just below the settlement of Morrison. Note in this section that the only human impact or settlement in 1874 is the town of Morrison itself.

Today this landscape is much different, especially to the east of the hogback. Colorado Highway 470 runs north-south along the foot of the hogback in the valley underlain by shales and weaker rocks, mostly the Cretaceous Pierre shale. Urban/suburban development has spread like an aggressive fungus from the Denver city center, twelve miles to the northeast, all the way to the foothills barrier of the hogback. Just on the eastern flank of the hogback sits Bandimere Speedway—a drag-racing venue undreamed of by Hayden and his crew. Morrison Road now cuts through the water gap as did a spur of the Denver and South Park Railroad put in around 1872.

Morrison has grown in the last century and a quarter, but not nearly at the rate of the megalopolis to the east; in 2000 the town had fewer than 500 residents. Probably its main attraction today is the amphitheater at Red Rocks Park—set amidst those scalloped rocks of the Fountain formation that seem to lean on the mountain front. This outdoor concert hall has been the site of innumerable national and international concerts, plays, and shows. It has seen everything from Bob Dylan retrospectives, to the Beatles, Jimi Hendrix, Aretha Franklin, Widespread Panic, and the Denver Symphony Orchestra.

What sets Morrison apart from other locales in Colorado are the extraordinary fossil remains located here that Hayden actually missed in his survey of the area. Those variegated shales of the Morrison formation were formed during the Jurassic period in earth’s history. During the Jurassic, in what is now Colorado, temperatures were very warm, the air was moist, and lush vegetation grew abundantly on the low-elevation land. This environment had the perfect set of ecosystems to provide for the emergence and evolution of the “terrible lizards,” what we call the dinosaurs.

The dinosaurs began their long tenure on earth during the very late Permian period (just at the end of the Paleozoic, or old-life era), but they flourished and spread during the Mesozoic era—the age of the reptiles and the era of middle life. Dozens of species developed from the Triassic into the Jurassic and even throughout the Cretaceous periods. Two taxa of dinosaurs developed: the Saurischia, with reptilian-like bone structures, and the Ornithischia, with birdlike skeletons. The Saurischia are further broken into the carnivorous dinosaurs, such the Velociraptor and Tyrannosaurus Rex, and the plant eaters, such as the Allosaurus and Camarasaurus. Each of these taxa has species that lived in ancient Colorado, and their fossils have been found throughout the state, many if not most of which have been encrusted in the Jurassic-age Morrison formation.

Hayden’s Survey never found examples of these fossils during its 1873–76 Colorado period. If the survey had discovered these ancient skeletons, some of the first dinosaur fossil digs in Colorado would have appeared on this sketch. The early discoveries actually came just after Hayden went on to work in other places. Othniel C. Marsh was notified by Arthur Lakes that Lakes had found an example of Titanosaurus montanus (changed to Atlantosaurus montanus), one of the very large plant eaters, in 1877 on the ridge just below the Dakota sandstone cap christened “Dinosaur Ridge.” This discovery and notification of Marsh and his archrival, Edward D. Cope, spurred Marsh to action.

Marsh immediately notified Lakes that he would pay handsomely for any and all dinosaur fossils found here. Other fossil remains discovered here include the Allosaurus, Diplodocus, and Brontosaurus (later named the Apatosaurus). Although Marsh and Lakes made many discoveries here, the quarrying was difficult because of the rock structure of the area. Subsequent superb fossil fields just north of Cañon City and even higher-quality and higher-quantity finds in northwestern Colorado and eastern Utah eventually overshadowed the Dinosaur Ridge site. But nearly all of the dinosaur finds throughout Colorado have been made in the Morrison formation.

Marsh’s fossil finds near Morrison are part of a darker and more human story played out in the salons of science during the last third of the nineteenth century. E. D. Cope, of the University of Pennsylvania and the Museum of Natural History in Philadelphia, was also a sometimes member of the Hayden Survey. He, like Marsh, was a paleontologist of considerable reputation. Like his scientific rival, Cope made his own discoveries of fossil dinosaur species—Coelophysis and Monoclonius, to name two—but his nondinosaur fossil finds were much more numerous and impressive. Paleontology during this period (and maybe still today) was a serious and competitive science. Monies from local, national, and international museums, the Smithsonian Institute, and myriad universities were doled out mainly by how many “first” finds were made by the individual in charge of the work. This financial incentive created an atmosphere where competition was heated; the intense competitions between the two were often called the “Bone Wars.” Marsh and Cope often claimed the first rights to the same fossil, they accused each other of stealing credit, they fought, they sometimes stretched the truth, and they were antagonists until their deaths. They were both scientific icons, and a scientist was either in Marsh’s camp or in Cope’s—no fence sitting was allowed. This put Hayden, who hired Cope for several field seasons, into a precariously delicate position especially when it came time to fight for funds from Congress and the White House. Both Marsh and Cope had influential friends in these lofty political places.

When you visit this beautiful and still relatively bucolic area, keep in mind the history of these scientific wars. Morrison, Colorado, is a small town, but its influence on field and museum science in the nineteenth century looms large.

© 2016 by University Press of Colorado

© 2016 by University Press of Colorado